Abstract

Facebook is one of the most popular social networking sites, but some call it a "fake book" (Mülle & Schulz, 2019). Hence to explore the phenomenon of fake identities, the study examined how Facebook users construct their identities and how much profile information is phoney. The study used a survey methodology, and 647 university students (252 male and 351 female) participated. Facebook has 14 fields of profile data against which respondents have answered on the Likert scale whether they disclose their accurate information. The study found that both male (mean score 1.9) and female (mean score 2.3) Facebook users create fake identities, but women create more fake identities than men.

Key Words

Facebook, Online Identity, Social Media Identity, Fake Profiles

Introduction

Internet Communication Technology has bridged the world, and now people here and far away are connected (Gralla, 1998). This connected world is called cyberspace, where people interact with one another, make friends, have discussions on topics of common interests, share their photos and activities, etc. (Perdew, 2014). Web 2.0 has gifted us the interactive version of the Internet, i.e., social networking sites, wikis, blogs, chat forums, and email facilities are some gifts of Web 2.0 (Bria, 2013).

Social networking sites have around 300 million consumers globally. Before smartphones, a computer device and internet connection were required for this connectivity. Now handsets have built-in fast internet service, and connectivity with peers in cyberspace has become easy (Rachakonda, 2016).

In the real world, an identifier is issued by the government in an identity card, driving license, and passport; in the cyber world, no such proof is required (Romanov et al., 2017). Computer-mediated communication allows users to create a virtual personality (Johnson & Miller, 1998).

In cyberspace, users decide how they would present themselves. Some share their accurate information, while some prefer anonymity over their original identity (Warburton, 2012). In this virtual world, creating identity is easy because no proof is required. A person can use a fake photo, address, profession, and other identity features (Perdew, 2014).

There are several reasons why people prefer to use anonymous or fake identities. For instance, Brennan and Pettit (2004) noted that people find it easy to express themselves when they are undercover. They are open to sharing their opinions and discussions when their identity is unknown (Kim 2012; Lange 2007; Papacharissi 2009), while some are shy with their real identity (McKenna et al., 2002). People may also create fake accounts for stalking, phishing, advertising, spamming, etc. (Wani et al., 2017).

Background

Roots of the Internet takes us back to a military project of the United States of America in the 1960s. This project was called Advanced Researched Project Agency. The said project sent and received the data packets with the help of computer technology (Lipschultz, 2020).

Wireless connectivity, called Wi-Fi, was invented in the 1980s; however, it came into proper utilisation in 1999. This wireless connectivity gave new horizons to the use of the Internet and connectivity among the people in the cyber world (Anniss, 2014).

During the 1990s, the Internet came into the general public's access, and they would connect through the Internet using a phone line and a modem (Ryan, 2011). Internet Realy Chat Client (mIRC) was the earliest program designed to exchange text messages, and mIRC did not require identification and allowed an anonymous chatting facility (van Doorn et al., 2008). In 2002 sixdegrees.com was launched as the first social networking site (Doser, 2018).

Now with the courtesy of smartphones, the Internet is in the hands of everyone. Who thought that Motorola's cell phone of 28 ounces (Woyke, 2014) would get so slim that everyone would carry it in their hands and pockets 24 hours a day.

Initially, mobile phones worked with narrow band technology to carry the voice. Over time the technology of 2G merged, which supported short message services and emails. The 2G technology helped a maximum of 9kbs of the data. During the 1990s, 3G technology was merged, supporting 2MB of data. With this advancement, users can use the Internet while walking, travelling, and performing daily house chores (Dahlman et al., 2010).

Fourth-generation technology supports 100 Mbs (Adibi, Mobasher, & Tofighbakhsh, 2009), and now 5G technology is ready to take over the Internet landscape with a data transfer rate of 10 Gbps (Rodriguez, 2015).

Web 1.0 had simple features like creating the content, sharing, and resharing it. While Web 2.0 is an interactive and advanced version that provides a suitable base for social networking sites (Bruns, 2008; Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010).

Lipschultz (2020) has explained that social networking sites have provided new ways of interaction. People can share information and content. Facebook has a wall, Twitter has a Feed, and Linkedin has an endorsement.

In 2004 Facebook and Myspace allowed their consumers to create customised profiles (Asur & Huberman, 2010). Mark Zuckerberg created Facebook with his friends, which students of Harvard used. It started with 650 students; after a month, 10,000 students joined this network. One in seven people has a Facebook account (Harris, 2012). The site is top-ranked, with 3 billion users who exchange 100 billion messages daily (Facebook, 2020).

Literature Review

This

study deals with the creation of fake identities. Let's see how various

scholars have defined "identity." Abrams and Hogg (2006) say

that identity is a fundamental concept of the people about themselves. Identity

is what they think they are. According to Deng (2011),

identity is how people relate themselves to their religion, caste, language,

culture, ethnicity, and race.

Hence

the concept of the person has two sides. One is what they are, and the other

one is what they would like to become. The thought of becoming their imagined

self is called fantasised self or the ideal self (Markus & Nurius, 1986).

Therefore, identity creation is a continuous process in which people create

their different identities to resolve their inner conflicts (Meryem, 2020).

Users on social networking sites feel free

to express themselves when their identities are not disclosed. They are

comfortable and even more open in an anonymous environment where they are not

identifiable (Brennan

& Pettit, 2004).

Alhabash et al. (2012)

measured seven motivations, i.e., (1) social connection (maintaining a

relationship, finding people, receiving friend requests, connecting and

reconnecting with the people), (2) shared identities (joining groups,

organisations, events, finding likeminded people), (3) photographs (tagging for

being tagged in the pictures, sharing the pictures, views the photos), (4)

content (playing games, participation in quizzes and using applications within

Facebook); (5) social investigation (meeting new people, going into an advance

search for people and stalking people), (6) social network surfing (checking

profiles of friends, probing profiles of others' friends, looking into profiles

of other people in general) and (7) status (for updating their status and for

looking that what others have on their status).

According to Romanov (2017), Facebook is a

big platform with 5-11% per cent of fake identities from 2013-to 14. Similarly,

Herzberg (n.d.) argues that around nine per cent of fake accounts on Fakebook

might have been cloned, compromised, and fabricated.

Da Silva (2017) noted that some fake

accounts had been created for data harvesting. These fake accounts become

friends with the people and steal their essential information.

Hermawati et al. (2021)

explored why fake accounts were created on Instagram. They concluded that

fantasies, low self-confidence, and escape from the social realities lead

teenagers to create fake identities.

Meryem (2020) explained that Netizens create

fake accounts to share photos and videos they do not own, for absurd

discussion, for passing nasty comments, for passing aggressive messages, for

defamation, for dating, and to fool others.

Alkawaz et al. (2020) noted that on

Facebook, respondents disclosed: 54% real name, age 37%, date of birth 75%,

Gender 81%, email 85%, contact number 15%, home address 11%, workplace and job

position 33%, interests 27%, family members 27%, relationship status 33%, 45 % actual

profile picture.

Zimmer (2010) argues

that having a fake name is deception, and only 3.8% of consumers had fake names

on Facebook. While Taraszow et al. (2010)

noted that 10% of their respondents share their phone numbers, 10% disclose

their city of living, and 54% identified their hometown.

Kwon et al. (2015) noted

that social network consumers adopt self-censorship while discussing politics. Rainie and Smith (2012) summed

that 22% of the users do not share their political views to avoid offending

someone, while 68% prefer silence on such discussion. While, Kaloydis, Richard, and Maas (2017)

argue that it is difficult to openly discuss religious beliefs on social

networking sites.

Southcott (2019) noted that gender plays a

vital role in the self-presentation of social networks because men are dominant

and open while women remain restricted. Similarly, Shafie et al. (2012) view

females as using attractive names while males use real names.

WU et al. (2015) argue

that photos on Facebook are a tool for self-presentation. Through photo

presentations, consumers illustrate their personalities. According to Wang et al. (2010), other

people in the network give importance to the photos in deciding whether they

want to initiate a relationship or not.

Kaskazi (2014) noted that some people create

fake Facebook identities to initiate romantic relationships. While Liu et al. (2013)

elaborate that people who disclose factual information about their sex,

relationship, address, and date of birth are at a higher risk that their

sensitive information could be leaked out.

Nosko (2010)

explains that social media users do not share their date of birth, name, and

contact information because they may feel insecure.

Wang and Kobsa (2009) argued

that some people do not want to share their professional information. Sometimes

it is because of their sensitivity and on-demand of the employer, while some

seek privacy.

Panek et al. (2018) noted

that people from different ethnicities have different disclosures in the about

me section. For instance, African-American users write more than white

Americans in the "about me" section.

People make friends on social networking

sites considering their mutual interests (Kiesbye, 2011).

Facebook users also join different groups to meet and discuss with like-minded

people.

Facebook users seek privacy and do not

disclose their activities on Facebook. They also think they might have to be

answerable if they reveal their activities

(Noelle-Neumann,

1993).

Froomkin (1999) argues

that going undercover and creating fake identities may give some people a sense

of protection, but it opens the doors to libel, spamming copyrights, and

illegal activities.

People

who use their real identities are more substantial and make healthier online

relationships (Marx, 1999). Therefore, Facebook also pushes its users to use

real names and photos and adopt real identities (Nagel & Frith, 2015).

Research

Gap

The study has been conducted to

fill the gap in the research undertaken by Wani et al. (2017). The researchers explained in

detail why fake identities are created. Still, the researchers didn't pinpoint

specific social networking sites and didn't quantify which account information

is inaccurate. Hence, this study has focused on Facebook and the 14 profile

data fields.

Research Questions

RQ

1:

Do Facebook users construct Fake identities?

RQ 2: Whether

male or female Facebook users construct more fake identities?

Based on the literature review,

the following constructs have to be measured for analysing fake identities on

Facebook.

Table

1.

Constructs

of the Study

|

Construct(s) |

Reference(s) |

|

Name |

(Zimmer, 2010) |

|

Phone Number |

|

|

City of Living |

(Taraszow et al., 2010) |

|

Native Town |

(Taraszow et al., 2010) |

|

Political Views |

(Kwon et al., 2015) |

|

Religious Views |

(Kaloydis et al., 2017) |

|

Gender |

(Southcott, 2019) |

|

Photo |

(WU et al., 2015) |

|

Relationship Status |

(Kaskazi, 2014) |

|

Activities |

(Noelle-Neumann, 1993) |

|

Date of Birth |

(Molema, 2010) |

|

Professional Information /

University Name |

(Wang & Kobsa, 2009) |

|

About Me |

(Panek et al., 2018) |

|

Interests |

(Kiesbye, 2011) |

Theoretical

Framework

On social media, consumers

actively create their profiles, post content of their choice, and interact with

others (Bruns, 2008; Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010).

This phenomenon is supported by the Uses and Gratification Theory (U&G) of

Mass Communication. Katz (1974) argues that U&G theory focuses on what

people do with the media and make choices. Fortner and Fackler (2014) explain

that U&G theory conceptualises the audience, focuses on people's actions,

and finds the needs sought and met.

Methodology

It is a quantitative research that measures variables using instruments by gathering numerical data, which is then examined using statistical methods. It looks for casual relationships and finds the association or relationship between the variables. (Creswell & Creswell, 2017).

The study's sample frame is students of Islamabad capital territory enrolled in universities recognised by the Higher Commission of Pakistan. According to the University-wise Enrolment of 2017-18, these universities have 1,65,086 students.

The study has applied a Proportionate sampling strategy - a method for gathering participants for a study). It is used when the population is composed of several subgroups that are vastly different in number. The number of participants from each subset is determined by their number relative to the entire population. The sample size is 1061 with a three per cent margin error and 95% confidence interval.

The study has used the survey method for gathering the data. The tool was designed on five points Likert scale.

Results

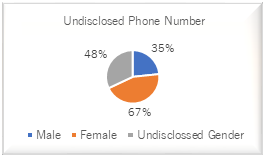

Figure 1

Facebook Users Who do not Disclose Phone Number

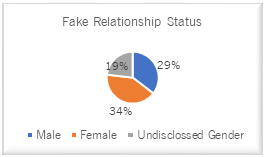

Figure 2

Facebook Users with Fake Relationship Status

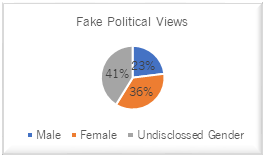

Figure 3

Facebook Users with Fake Political Views

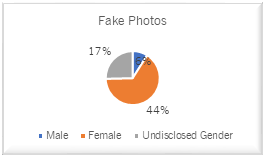

Figure 4

Facebook users with Fake Photos

Figure 5

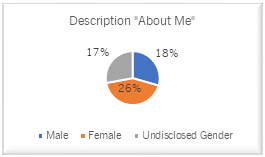

Facebook Users with the Fake Description "about me"

Figure 6

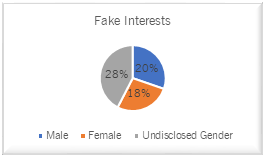

Facebook Users with Fake Interests

Figure 7

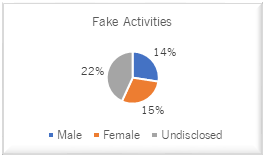

Facebook Users with Fake Political Activities

Figure 8

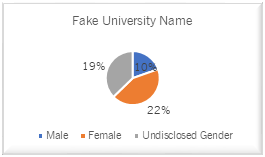

Facebook Users with Fake University Names

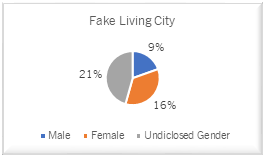

Figure 9

Facebook Users with the Fake Living City

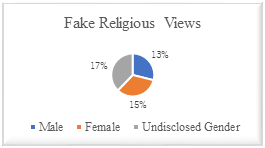

Figure 10

Facebook Users with Fake Religious Views

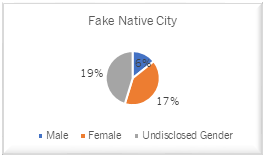

Figure 11

Facebook Users with Fake Native City

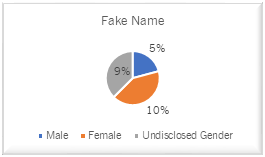

Figure 12

Facebook Users with a Fake Name

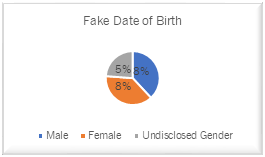

Figure 13

Facebook Users with a Fake Date of Birth

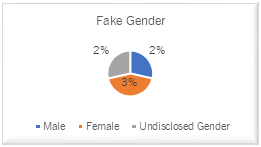

Figure 14

Facebook Users with a Fake Gender

Results

Following are the mean scores of

males, females, and those who did not disclose their gender, explaining the

creation of fake identities on Facebook.

Table

2.

Mean Score for Constructing Fake Identities

|

Gender |

Mean Score for Fake

Identities |

|

Males |

1.9 |

|

Females |

2.3 |

|

Undisclosed Gender |

2.1 |

Conclusion

Both male and female Facebook users construct

fake identities, but female users create more fake identities than males.

References

- Abrams, D., & Hogg, M. A. (2006). Social identifications: A social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. Routledge.

- Alhabash, S., Park, H., Kononova, A., Chiang, Y. H., & Wise, K. (2012). Exploring the Motivations of Facebook Use in Taiwan. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(6), 304–311.

- Anniss, Matt. (2014) How does a network work? Gareth Stevens Publishing

- Brennan, G., & Pettit, P. (2004). Esteem, ldentifiability and the Internet. Analyse & Kritik, 26(1), 139–157.

- Teixeira Da Silva, J. A. (2017). Fake peer reviews, fake identities, fake accounts, fake data: beware! AME Medical Journal, 2, 28.

- Dahlman, E., Parkvall, S., Skold, J., & Beming, P. (2010). 3G evolution: HSPA and LTE for mobile broadband. Academic press.

- Deng, F. M. (2011). War of visions: Conflict of identities in the Sudan. Brookings Institution Press.

- Facebook. (2020). Facebook Statistics 2. Available at:

- Froomkin, A. M. (1999). Legal Issues in Anonymity and Pseudonymity. The Information Society, 15(2), 113–127.

- Gralla, P. (1998). How the Internet works. Que Publishing.

- Hermawati, T., Setyaningsih, R., & Nugraha, R. P. (2021). Teen Motivation to Create Fake Identity Account on Instagram Social Media. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 8(4), 87.

- Johnson, D. G., & Miller, K. (1998). Anonymity, pseudonymity, or inescapable identity on the net (abstract). ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society, 28(2), 37–38.

- Kaloydis, F. O., Richard, E. M., & Maas, E. M. (2017). Sharing political and religious information on Facebook: coworker reactions. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 6(2), 239-270.

- Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68.

- Khoshsabk, N., & Southcott, J. (2019). Gender Identity and Facebook: Social Conservatism and Saving Face. The Qualitative Report 24(4), 632-647.

- Kiesbye, S. (Ed.). (2011). Are Social Networking Sites Harmful?. Greenhaven Press.

- Kim, S. H. (2012). Testing Fear of Isolation as a Causal Mechanism: Spiral of Silence and Genetically Modified (GM) Foods in South Korea. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 24(3), 306–324.

- Kwon, K. H., Moon, S. I., & Stefanone, M. A. (2014). Unspeaking on Facebook? Testing network effects on self-censorship of political expressions in social network sites. Quality & Quantity, 49(4), 1417–1435.

- Lange, P. G. (2007). Publicly Private and Privately Public: Social Networking on YouTube. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 361–380.

- Lipschultz, J. H. (2020). Social media communication: Concepts, practices, data, law and ethics. Routledge.

- Liu, C., Ang, R. P., & Lwin, M. O. (2013). Cognitive, personality, and social factors associated with adolescents' online personal information disclosure. Journal of adolescence, 36(4), 629-638.

- Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American psychologist, 41(9), 954.

- McKenna, K. Y., Green, A. S., & Gleason, M. E. (2002). Relationship formation on the Internet: What's the big attraction?. Journal of social issues, 58(1), 9-31.

- Müller, P., & Schulz, A. (2019). Facebook or Fakebook? How users’ perceptions of ‘fakenews’ are related to their evaluation and verification of news on Facebook. Studies in Communication and Media, 8(4), 547–559.

- Noelle-Neumann, E. (1993). The spiral of silence: Public opinion--Our social skin. University of Chicago Press.

- Nosko, A., Wood, E., & Molema, S. (2010). All about me: Disclosure in online social networking profiles: The case of Facebook. Computers in human behavior, 26(3), 406- 418.

- Panek, E., Nardis, Y., & Auverset, L. (2018). It's All about Me (or Us): Facebook Post Frequency & Focus as Related to Narcissism. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 7(2), 1-17.

- Papacharissi, Z. (2009). The virtual geographies of social networks: a comparative analysis of Facebook, LinkedIn and ASmallWorld. New Media & Society, 11(1–2), 199–220.

- Perdew, L. (2014). Online Identity. Abdo.

- Rainie, L., & Smith, A. (2012). Social networking sites and politics. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved June, 12, 2012.

- Ryan, P. (2011). Social networking. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

- Shafie, L. A., Nayan, S., & Osman, N. (2012). Constructing identity through facebook profiles: Online identity and visual impression management of university students in Malaysia. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 65, 134-140.

- Taraszow, T., Aristodemou, E., Shitta, G., Laouris, Y., & Arsoy, A. (2010). Disclosure of personal and contact information by young people in social networking sites: An analysis using Facebook profiles as an example. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 6(1), 81–101.

- Van Doorn, N., Wyatt, S., & Van Zoonen, L. (2008). A body of text: Revisiting textual performances of gender and sexuality on the Internet. Feminist Media Studies, 8(4), 357-374.

- Wang, S. S., Moon, S. I., Kwon, K. H., Evans, C. A., & Stefanone, M. A. (2010). Face off: Implications of visual cues on initiating friendship on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(2), 226-234.

- Wani, M. A., Sofi, M. A., & Wani, S. Y. (2017). Why Fake Profiles: A study of Anomalous users in different categories of Online Social Networks. International Journal of Engineering Technology Science and Research, 4 (9), 320-329.

- Warburton, S. (Ed.). (2012). Digital identity and social media. IGI Global.

- Woyke, E. (2014). The Smartphone: Anatomy of an industry. The new press.

- Wu, Y. C. J., Chang, W. H., & Yuan, C. H. (2015). Do Facebook profile pictures reflect user’s personality? Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 880–889.

- Zimmer, M. (2010). Facebook's Zuckerberg: "Having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity.". Michael Zimmer, 14.S

Cite this article

-

APA : Taj, S., & Shah, B. H. (2022). Creation of Fake Identities on Social Media: An Analysis of Facebook. Global Digital & Print Media Review, V(II), 44-52. https://doi.org/10.31703/gdpmr.2022(V-II).05

-

CHICAGO : Taj, Sohail, and Babar Hussain Shah. 2022. "Creation of Fake Identities on Social Media: An Analysis of Facebook." Global Digital & Print Media Review, V (II): 44-52 doi: 10.31703/gdpmr.2022(V-II).05

-

HARVARD : TAJ, S. & SHAH, B. H. 2022. Creation of Fake Identities on Social Media: An Analysis of Facebook. Global Digital & Print Media Review, V, 44-52.

-

MHRA : Taj, Sohail, and Babar Hussain Shah. 2022. "Creation of Fake Identities on Social Media: An Analysis of Facebook." Global Digital & Print Media Review, V: 44-52

-

MLA : Taj, Sohail, and Babar Hussain Shah. "Creation of Fake Identities on Social Media: An Analysis of Facebook." Global Digital & Print Media Review, V.II (2022): 44-52 Print.

-

OXFORD : Taj, Sohail and Shah, Babar Hussain (2022), "Creation of Fake Identities on Social Media: An Analysis of Facebook", Global Digital & Print Media Review, V (II), 44-52

-

TURABIAN : Taj, Sohail, and Babar Hussain Shah. "Creation of Fake Identities on Social Media: An Analysis of Facebook." Global Digital & Print Media Review V, no. II (2022): 44-52. https://doi.org/10.31703/gdpmr.2022(V-II).05