Abstract

The content analysis is used to quantitatively analyze the portrayal of the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) in leading English language dailies of Pakistan, Dawn, The News International and Express Tribune, for three (3) months, from 22 February 2022 to 22 May 2022. The News International seems to portray Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) more when compared with Dawn and Express Tribune. All three newspapers emphasize freedom of expression, and no newspaper adopts the stance toward censorship or regulation of media. However, The Expression Tribune does hint at the need for censorship in one news article. The Dawn newspaper also emphasizes the voice of opposition and legal proceedings. The study is likely to have implications for the socially responsible role of mass media in contexts of factual news and the emerging issue of fake news by the inclusion of diverse voices. Unfortunately, the selected newspapers did not show cultural pluralism.

Key Words

Portrayal, Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (PECA), English Dailies, Freedom of Expression, Censorship, Voices

Introduction

Before the by-election in 2022, there was passed a vote of no confidence against the then Prime Minister of Pakistan. Earlier, the Pakistan Democratic Movement or commonly known as PDM, had started a campaign against the government. During this political crisis and tug of war, the opposition and the Government of Pakistan (GOP) passed an ordinance to make changes to the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA). The purpose of making amendments was to protect authorities, including military and judicial figures to ensure trust in institutions and to avoid the clash of institutions. The defamation of these institutions and authorities was considered a criminal offence according to these suggestions or amendments made in PECA. There were also suggested penalties along with these recommendations.

Prime Minister of Pakistan, Mr Imran Khan Niazi, argued that changes in ‘PECA’ were suggested to stop social media from inappropriate content, which he labelled as filth on social media in his media briefings. The argument put forward by Imran Khan had merit because of the incidents of ‘Tik Tok’ stars becoming famous by hook and crook. The private life of individuals is not safe on social media. The first lady and the wife of Mr Imran Khan were also not safe from personal attacks by social media users. YouTube and Facebook, in particular, were found to be more sensational by portraying the personal lives of political and showbiz personalities in indecent ways.

There is criticism of ‘PECA’ by Nadia Rahman. Rahman is the acting deputy regional director for South Asia at Amnesty International. Rahman argues that “PECA has been used to silence freedom of expression on the pretext of combining fake news, cybercrime and miss-information”. The media analysts also showed mixed responses towards the amendments in 'PECA'. But the majority of them seemed neutral because 'PECA' was also a threat to the freedom of mass media and the journalists. Some saw it as a dictatorship because the government had not consulted with the journalists to make such amendments.

It is interesting to note that Pakistan has already ratified the ‘International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights' or 'ICCPR'. Article 19 of this document allows for restrictions on freedom of expression to protect the "individual reputation". However, at the same time, "ICCPR" argues that the restrictions must be necessary and narrowly defined ("Pakistan's cyber-gag law PECA under fire: Report,” 2022).

Mass media can never be objective or neutral because objectivity is not attainable to its fullest, especially when various institutions are clashing for their rights. In the case of PECA, governmental authorities were protecting themselves by winning the trust of the people by curbing the alternative points of view. The critics were of the view that the government was becoming unpopular. Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf was popular on social media, but because of inflation, the then government was losing the trust of the people and wanted to control social media by blocking or censoring the voices of the vulnerable. However, that was just an allegation against the government in the backdrop of the poor performance of the government after the devastation of the Corona Virus and the fracturing economy. The stance of the government on 'PECA' was overshadowed by the corona, economic crisis and the struggling government. The opposition and "PDM" took advantage of the situation and also criticized the government on their stance of making amendments in 'PECA'. The opposition was of the view that the then government was trying to build barriers against other political parties to raise their voice against inflation. In this way, the issue became political and not neutral and objective. Over the years, journalists have also seen to take sides with certain political parties. On the other hand, the media and journalists started protecting their freedom. There were vested interests of the opposition and media persons sitting in media houses. However, the voice of the people is less heard in sensational headlines of the news. The objectivity in media demands that the mass media should cover all voices, but unfortunately, it does not happen in various situations and contexts. The mass media, in this way, may compromise their socially responsible role by not including all voices and emphasizing on few. This results in a cultural deficit of diverse competing voices. Cultural diversity ensures that the mass media include all voices to present a balanced, neutral and objective coverage.

In the light of this background, the current study researches the coverage in leading Pakistani liberal dailies about the portrayal of amendments in PECA or “PECA Ordinance” and specifically analyzes the portrayal in contexts of coverage, freedom of expression, censorship, governmental versus opposition voices, the debate about civil versus criminal penalties and solutions within. It is to explore whether the leading liberal newspapers in Pakistan fulfil their socially responsible role by providing balance in news coverage by informing the educated class of Pakistan by providing critical reflections.

The objectives of the study are to analyze: (1) The portrayal in contexts of the extent of coverage of PECA in leading liberal English language dailies of Pakistan, (2) Portrayal in the context of freedom of media or freedom of expression and media, (3) Portrayal in context of censorship of media, (4) Portrayal in context of voices of government, judiciary and opposition, (5) Portrayal in context of civil and criminal penalties and suggestions within.

Literature Review

Keane (1991) argues that media should provide space for people to decide between good and evil, the mass media should protect individual rights along with elite ones, and falsehood should be checked. This is only possible when the media perform their socially responsible role of informing people.

The Microsoft Corporation (MC) removed the site of Beijing blogger from MSN Spaces services, and that was done in 2005, other American companies also joined MC in assisting in China's Internet censorship, but media analysts and the judiciary, especially in America, started criticizing these commercial organizations (Stevenson, 2007).

In the democratic systems of government, the mass media act as watchdogs on the government for efficient working. Whitten-Woodring (2009) argues that the effect of media freedom on political government's respect and inclination towards human rights is negatively correlated in countries with dictatorship. However, this association is positive in countries with a democratic system of governance.

Charron (2009) argues that the countries in which there is press freedom, those countries are dealing effectively with corruption with political and social openness.

The 'Radical Libertarians', also known as 'First Amendment Absolutists', are of the opinion that the media should be free and independent of any laws means that no laws should govern the media or, in simple notion, the media should be unregulated (Baran & Davis, 2010).

Nam (2012) studied the effects of freedom of information legislation on press freedom by analyzing different countries in the world. It is found to have a strong effect of the former variable on the latter in the advanced industrial democracies.

Camaj (2013) find a strong association between media freedom and corruption in countries with a parliamentary system of government. Jan, Riaz, Siddiq and Saleem (2013) explore coverage patterns of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf in two leading English language dailies of Pakistan and contribute to agenda setting framework by reporting that The News International gave more coverage to PTI when compared with Dawn newspaper. Further, Dawn, in comparison to The News International, remained neutral.

Stanig (2014) argues that exploitive defamation laws in certain nations disturb the extent of information about corruption which mass media report. Freedom of expression means the provision and availability of correct and precise pieces of information to people or the public is available at the mass level without the fear or force of censorship or punishment (Beyer, 2014). The freedom of expression is not an absolute right and may collide with sensual or sexually explicit material, the levels of hate speech within and outer groups, and the sentiments of anti-governmental stances against the democratic government or even the security agencies. These types of phenomena have compelled governments around the globe to limit free expression and to use some regulatory actions against these sentiments and sensational contents (Akdeniz, 2010) by safeguarding the national interest and sovereignty.

Starke, Naab, and Scherer (2016) report that the freedom of media, access to internet technology, and the availability of the online services provided by the government reduce corruption in the respective countries a great deal.

Imre, Pjesivac and Luther (2016) did a thematic analysis of the news items about Wiki-Leaks and Internet freedom of expression in newspapers of Great Britain (The Guardian), France (Le Monde), Australia (The Sydney Morning Herald), and China (The China Daily). It was found that the newspapers supported Internet freedom as well as the actions of Wiki-Leaks and Julian Assange while criticizing U.S. attempts to suppress the online organization and its founder.

Jha and Sarangi (2017) find a strong association between the penetration of Facebook and corruption in countries with low press freedom.

Administrative censorship is a kind of censorship in which the state affects the councils of media companies to dictate an editorial decision in line with the statements of politicians and their political stances (Gonzalez-Quinones & Machin-Mastromatteo, 2019). The amendments in PECA are seen as administrative censorship.

Toor (2020) contributed to agenda setting theory by content analyzing the leading English and Urdu language dailies of Pakistan to explore the portrayal of political parties in Pakistan. It was explored that PML (N) was given the maximum editorial and news coverage regarding important national issues from 2008 to 2013. It is interesting to note that Pakistan Peoples’ Party (PPP) was ruling at that time, but PPP was given the second major portrayal.

Shahzad, Saleem and Sarwar (2021) extended the propaganda model by Herman and Chomsky and analyzed the coverage in Dawn and The News International. Shahzad (2021) argued that the latter newspaper made more propaganda.

Jamil (2021) argued that new media dictators utilize information overload and un-real social media log-ins for propaganda in a new media age. First, this has fueled up polarization of opinion; second, it has enabled even people to control information.

Jamil (2021) emphasizes that it is important to clarify the rationale for censorship of new media, censorship of any specific website, or exclusion of any content which is posted or uploaded. It is suggested by Jamil (2021) that the removal of content in the new media space should follow a strong rationale or the justification by the authority, which is judicial as well as impartial. This kind of censorship, according to him, should be free from implicit or explicit pressures, which may include political or even commercial pressure.

Theoretical Framework

The study utilizes the agenda-setting theory and the social responsibility theory. The rationale for the selection of agenda setting theory is that it explores the mass media effects. Baran and Davis (2010) argue that the idea of agenda setting has origins in the era of penny pres. The idea of agenda-setting is also reflected in the argument of Lippman (1992), who argued that "people respond to pictures in their heads". But, it was Cohen (1963) who expanded the previous ideas and organized ideas in the form of agenda setting. Cohen (1963) argued that: "It (press) may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about. In short, the journalists, like the editors of the newspapers, make a plan by placing events and personalities in the factual and opinioned genres. The factual genres include the front page news stories. The opinioned genres include the editorial, column, editorial cartoon and letters to the editor.

The second theory being utilized is the social responsibility theory. Curran (1991) argues that the Hutchins Commission’s Report asked the journalistic community to: commit to goals of neutrality, adoption of procedures for ‘verification-of-facts’, adding different sources of information by presenting opposing explanations (diverse voices), and mass media’s role to inform by reducing the sensational effect of media. The ideas presented in the 'Hutchins Commission Report' are also known as 'Social Responsibility Theory'. The Social responsibility theory emphasizes the need for an independent press which becomes the voice of all people (cultural pluralism), not the voice of a few elites or a handful of groups (Baran & Davis, 2010).

The theories of agenda setting and the social responsibility theory have relevance to the issue of amendments in PECA. The media should adhere to the norm of social responsibility by adding various voices, whether political, legal or public, to encourage cultural pluralism. It is in this context the following research questions are formulated to research the agenda-setting function of media by analyzing the cultural diversity in the news of leading dailies of Pakistan.

RQ1. What is the extent of coverage of PECA in Dawn, Express Tribune and The News International?

RQ2. What is the extent of coverage in relation to freedom of expression when discussing PECA in Dawn, The News International and Express Tribune?

RQ3. What is the extent of coverage in relation to censorship of media when discussing PECA in Dawn, The News International and The Express Tribune?

RQ4. Which voices are covered by Dawn, The News International, and The Express Tribune when discussing PECA?

RQ5. Which among the civil and criminal proceedings being covered by the Dawn, The News International and Express Tribune when discussing PECA?

Methodology

The quantitative content analysis method is used to analyze the portrayal of the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) in leading dailies of Pakistan. The universe for the study is 3 months, from 22 February to 22 May 2022. The rationale for selecting this time period is that the media had highlighted the amendments in Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act. The purposive sampling technique is used to select the three English language elite newspapers. The rationale for the selection of these newspapers is that they are liberal and are read by decision-makers and the educated class of the country. The independent variables for the study are Dawn, The Express Tribune, and The News International. The dependent variables for the study are the overall extent of coverage, the extent of coverage in relation to freedom of expression, the extent of coverage in the context of coverage of censorship, the extent of coverage in the context of voices, extent of coverage in the context of civil and criminal proceedings. The variables are measured on a nominal scale. The genres or the units of analysis selected are front-page news stories, editorials, columns, editorial cartoons and letters to the editor. The frequency and percentage are used for the analysis of data by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.

Results

The total number of articles

which appeared in the newspapers was 49.

Table

1.

The portrayal of PECA in Pakistani Dailies (N = 49)

|

|

Dawn |

The News International |

The Express Tribune |

|||

|

|

f |

% |

f |

% |

f |

% |

|

Extent

of Coverage |

16 |

33% |

18 |

38 |

15 |

29 |

|

Emphasis

on Freedom of Express |

13 |

27% |

15 |

31% |

12 |

24% |

|

Emphasis

on Censorship |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

- |

|

Governmental Voice |

8 |

16% |

10 |

20% |

7 |

14% |

|

Judicial Voice |

14 |

29% |

12 |

24% |

11 |

22% |

|

Voice

of Opposition |

14 |

29% |

11 |

22% |

10 |

20% |

|

Civil

or Criminal Proceedings |

15 |

31% |

14 |

29% |

15 |

31% |

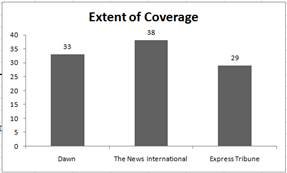

Figure 1

The extent of Coverage in Percentage in Context of PECA in Leaning English Language Dailies of Pakistan.

The News International seems to portray Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) more when compared with Dawn and Express Tribune.

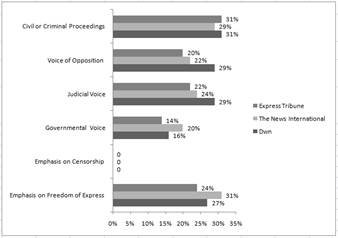

Figure 2

All three newspapers emphasize freedom of expression, and no newspaper adopts the stance toward censorship of media. The News International uses political voices more when comparing Dawn and The Expression Tribune. The Dawn newspaper seems to cover the judicial voices more when compared with The News International and The Express Tribune. The Expression Tribune does highlight the need for censorship. The Dawn newspaper also emphasizes the voice of opposition and legal proceedings.

Conclusion and Implications

The selected newspapers do provide the coverage by emphasizing the legal and political voices; however, the alternative discourse of censorship and regulation of fake news is missing, although Expression Tribune does highlight it in one article about the discussion of censorship of content. The norm of social responsibility demands the discussion of issues in a neutral way, and Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act could be debated in parliament, but it could not be because of a political crisis. The newspapers seemed to talk about their right to freedom of expression and thought that PECA is a law based on dictatorship and any changes in it would be a breach of media freedom. The change of government also resulted in a change in the nature of legal proceedings in the context of amendments in the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (PECA). The newspapers are also silent on PECA now. The momentum that newspapers had gained could be accelerated to discuss the nature of fake news and regulate it in contexts of privacy issues.

References

- Akdeniz, Y. (2010). To block or not to block: European approaches to content regulation, and implications for freedom of expression. Computer Law & Security Review, 26(3), 260–272.

- Beyer, J. L. (2013). The Emergence of a Freedom of Information Movement: Anonymous, WikiLeaks, the Pirate Party, and Iceland. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(2), 141–154.

- Camaj, L. (2013). The media’s role in fighting corruption: Media effects on governmental accountability. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18(1), 21-42.

- Charron, N. (2009). The Impact of Socio-Political Integration and Press Freedom on Corruption. Journal of Development Studies, 45(9), 1472–1493.

- Cohen, B. C. (1963). The Press and Foreign Policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Curran, J. (1991). Mass media and democracy: A reappraisal. Mass media and society, 2, 82- 117.

- Davis, D. K., & Baran, S. J. (2010). Mass communication and everyday life: A perspective on theory and effects. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- González-Quiñones, F., & Machin- Mastromatteo, J. D. (2019). On media censorship, freedom of expression and the risks of journalism in Mexico. Information Development, 35(4), 666–670.

- Imre, I., Pjesivac, I., & Luther, C. A. (2016). Governmental control of the Internet and WikiLeaks: How does the press in four countries discuss freedom of expression? International Communication Gazette, 78(5), 385–410.

- Jamil, S. (2021). The rise of digital authoritarianism: Evolving threats to media and Internet freedoms in Pakistan. World of Media. Journal of Russian Media and Journalism Studies, 3(3), 5–33.

- Jan, M., Riaz R, M., Siddiq, M., & Saleem, N. (2013). Print media on coverage of political parties in Pakistan: Treatment of opinion pages of ‘The Dawn’ and ‘News’. Gomal University Journal of Research, 29(1),

- Jha, C. K., & Sarangi, S. (2017). Does social media reduce corruption? Information Economics and Policy, 39, 60–71.

- Keane, J. (1991). The media and democracy. Cambridge.; Polity Press.

- Lippman, W. (1992). Public Opinion. New York: Macmillan.

- Nam, T. (2012). Freedom of information legislation and its impact on press freedom: A cross-national study. (4), 521–531.

- Shahzad, K., Saleem, N., & Sarwar, M. S. (2021). Overtness vs Covertness: Operations of Propaganda Model Filters in Pakistani Newspapers. Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan, 58(2),

- Stanig, P. (2014). Regulation of Speech and Media Coverage of Corruption: An Empirical Analysis of the Mexican Press. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 175–193.

- Stevenson, C. (2007). Breaching the great firewall: China's internet censorship and the quest for freedom of expression in a connected world. BC Int'l & Comp. L. Rev., 30,

- Toor, S. I. (2020). Comparative Analysis of the Portrayal of PPPP, PML (N) and PTI in Pakistani Print Media during Democratic Tenure of PPPP. Global Political Review, 5(3), 90–99.

- Whitten-Woodring, J. (2009). Watchdog or Lapdog? Media Freedom, Regime Type, and Government Respect for Human Rights. International Studies Quarterly, 53(3), 595– 625.

Cite this article

-

APA : Bajwa, A. M., Hussain, M., & Arif, M. (2022). Portrayal of Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act in Leading Liberal Dailies of Pakistan. Global Digital & Print Media Review, V(II), 105-111. https://doi.org/10.31703/gdpmr.2022(V-II).10

-

CHICAGO : Bajwa, Amir Mehmood, Mudassar Hussain, and Maham Arif. 2022. "Portrayal of Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act in Leading Liberal Dailies of Pakistan." Global Digital & Print Media Review, V (II): 105-111 doi: 10.31703/gdpmr.2022(V-II).10

-

HARVARD : BAJWA, A. M., HUSSAIN, M. & ARIF, M. 2022. Portrayal of Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act in Leading Liberal Dailies of Pakistan. Global Digital & Print Media Review, V, 105-111.

-

MHRA : Bajwa, Amir Mehmood, Mudassar Hussain, and Maham Arif. 2022. "Portrayal of Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act in Leading Liberal Dailies of Pakistan." Global Digital & Print Media Review, V: 105-111

-

MLA : Bajwa, Amir Mehmood, Mudassar Hussain, and Maham Arif. "Portrayal of Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act in Leading Liberal Dailies of Pakistan." Global Digital & Print Media Review, V.II (2022): 105-111 Print.

-

OXFORD : Bajwa, Amir Mehmood, Hussain, Mudassar, and Arif, Maham (2022), "Portrayal of Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act in Leading Liberal Dailies of Pakistan", Global Digital & Print Media Review, V (II), 105-111

-

TURABIAN : Bajwa, Amir Mehmood, Mudassar Hussain, and Maham Arif. "Portrayal of Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act in Leading Liberal Dailies of Pakistan." Global Digital & Print Media Review V, no. II (2022): 105-111. https://doi.org/10.31703/gdpmr.2022(V-II).10