Abstract

Technological networks have established a new social morphology of the modern world. The paper provides an understanding of the notion of the networked public sphere by examining all the seminal notions to theorize the ‘Networked Public Sphere’. The paper reflects that the boundaries between old and new media have been blurred and the new media technologies have established a hybrid environment in which there is a huge interplay between conventional media and new media. The paper concludes that the political use of social media among citizens in the networked public sphere helps to devise strategies to be engaged in online and offline political activities and generate a public discourse among them that influence the political domains of the society.

Key Words

Public Sphere, Social Media, Political Activism, Networked Public Sphere

Introduction

Haberm’ Public Sphere

The first notion of the Public Sphere was given by Jurgen Habermas (1962). The public sphere is regarded as a public planetary between the government and a private-public institution where debate and discussion take place in order to form a public opinion (Habermas, 1989). The public sphere is one of the cardinal socio-political elements of society where citizens discuss their independent views and attempt to influence the course of action of the state. According to him, the public sphere is a platform where individuals sit together and discuss the problems of their society and through this platform; they try to influence the political actions of a democratic system (Habermas, 1996).

The public sphere has generally been regarded as a podium that is core to the existence of a legitimate democratic system, where individuals can freely exchange their views on different socio-economic and political matters and observe the free flow of public discussion. It is an informal space where groups and individuals assemble to have a deliberate dialogue on societal problems, discuss matters to their mutual interests and try to reach shared solutions to the issues. The public cafes, restaurants, and public squares serve as meeting assemblies where people assemble to discuss different issues of society. Such discussions are given weightage by political authorities and have a considerable influence on their decision-making process. These public spheres serve the primary purpose of participatory democracy underscoring the extensive contribution and assistance of citizens in the operation of the political system of the society. This sphere finds an open media territory that is vital to establish such societies that help to build an accountable structure of real democracy and governance. Hence, the idea of the public sphere as theorised by Jurgen Habermas bears a normative discipline in order to function as a democratic system.

Functions of Habermas Public Sphere

Since the researcher cannot reflect upon the full exegeses of his notion of the public sphere due to the demands of the current study, a limited attempt was made to conceptualise the social function of Habermas's public sphere.

According to Habermas (2006), a truly deliberative democracy needs a social system and a communication model. He expounded how mediated communication helps the political system to fulfil the standardised objectives of deliberative democracy. At the core of this deliberative democracy is the public sphere whose job is to filter the distributed opinion. This public sphere obtains and allows only the considered opinion to pass through it. Habermas, while putting this filtering practice from the social systemic perspective, defined the public sphere as an intercessor organism that functions between a formal and informal discussion in amphitheatres at both ends (top and bottom) of the political system.

For a true public sphere model, independent media and communication reflexivity are mandatory. Independent media means it should be self-regulatory, and autonomous, and should be influenced by political actors, market forces, and internal and external interest groups. Communication reflexivity demands that the public sphere must provide a mechanism through which public opinion can reach upwards from civil society to the political public sphere where political decisions are made and elite opinion is formed. The public sphere ideally filters the general public opinion in order to provide a platform where only considered public opinion is entertained (Habermas, 2006).

The social system defined by Habermas comprised three macro-social systems: the political system (governmental institutions), the functional system (economy, education, energy, etc.), and the civil society (community of citizens). Under the norms of the public sphere, the political system is bound to accept the demands that stem from the other two macro-social systems. The chief purpose of civil society is to deliver the problems of the citizens to the political system of the society (Habermas, 1996). He has categorically created a divisional line between the public sphere and the three macro-social systems. He maintained that the public sphere has two outputs: public opinion and communicative power. He asserted that an efficient and autonomous public sphere, after filtering public opinion, manages to circulate only the considered public opinions. The second output of the public sphere which provides to influence the political system is the communicative power of the civil society that backs the considered public opinion (Habermas, 2006). He further explains that communicative power is the communicatively generated power that is different from the administratively employed power of the political system.

The governmental institutions exercise the administratively employed powers under the rules and regulations made by the legislatures, whereas the communicatively generated powers are used by the civil society to act in an integrated way under the mutual understanding occurring in the interpersonal relationship among the members of the civil society. He termed administratively employed powers as steering forces that intend to influence the mindset of the voters and consumers in the public sphere by the deployment of mass media in order to drill conformist behaviours among the citizens (Habermas, 1996). In contrast, communicative power is termed as a counter-steering force that aims to stimulate cooperation and mutual understanding between the components of civil society.

Networked Public Sphere

Manuel Castells (1996) in his book asserted that technological networks had established a new social morphology of the modern world. He viewed that in a network society, electronically administered information grids constitute the key features of social activities and their configurations. According to him, although networks are ancient practices of public organisations, they have acquired a fresh life in the age of information by converting them into information networks advanced by information and communication technologies. These technologies provide an interactive atmosphere where coordination and cooperation are possible through communication and feedback within the networks (Castells, 2000). The Internet provides a platform to private citizens and enables them to interact with the political elite regardless of their status, and common peers where they get an opportunity to get information and voice their problems (Castells, 2008).

Social networks have been modified in terms of processing and managing information by using microelectronic-based technologies. Subsequently, this leads towards an involuntary revision of the operationalisation of the processes of modern society. Castells (2000) argued that the modern world does not depend entirely upon technology to alter the old forms of social networks; instead, the modification of the social network is also contingent upon the economic and socio-political factors that shape the incarnation of the network society.

The existing communication model in the contemporary world has been changed by informational societies, which are bolstered by new information and communication technologies. According to Cardoso (2008), the conventional mass communication model has been replaced by a networked communication model. Unlike the model of mass communication, which is established around the concentrated system of media hierarchy and a large audience, the networked communication model is advanced by new emerging communication technologies that help the audience to establish new networks or to link up with existing networks. He stresses that the contact between media and society should be viewed through a networked model as the individuals while using social media technologies, is driven by the logic of networking where the consumption of diverse media systems are combined to achieve intended goals.

Today, with the advent of ICTs, these public spheres have been transformed from public cafes into new high-tech virtual groups via the Internet and social networking sites as discussed by the proponents of the “Network Society”. Papacharissi (2002) endorsed his notion and affirmed that the Internet had converted the public sphere from physical virtual communication. He asserted that media technologies have become advanced to such an extent that the new media appears as normal media, replacing paper with telecommunication technologies as means of communication. He further argued that these communication technologies are used by larger sections of societies for their vested social, economic, and political interests.

According to Benkler (2006), the networked public sphere brought a shift from the commercially controlled small number of media conglomerates to a forum, which is reachable to and produced by individuals. He maintained that the networked public sphere empowers the users to open their voices to share their reservations and viewpoints with the world. They do so in such an independent way that cannot be corrupted by money, control, or influence of the mass media owners and other pressure groups. Many theorists had shown their consent regarding the democratic nature of social media which offers a marketplace which is more independent and self-driven where citizens can generate a wider range of opinions and viewpoints without any pressure (Benkler, 2006; Jenkins, 2006). Today, citizens not only craft content for social media but also shed light on others’ content by commenting and sharing their version of the news, making it more democratic and pluralistic. As a result, a new inclusive and wider public sphere has been established, which is contrary to a traditional corporate public sphere that originated from the elite journalists of mainstream media.

Jenkins et al. (2006) argued that the public sphere multiplies the variety of voices and enables them to be heard by the authorities. Therefore, the expansion of communication outlets is vital in this utopian digital public sphere model. Jenkins maintained that analogue media (e.g., New York Times) is more authoritative and political compared to digital media (e.g., YouTube), which is more liberal and less political.

The networked public sphere is considered an open and multifaceted network of opinions and arguments about issues related to the public. It has been recognised as an entity that develops public opinion and political judgment of the people through which they adjust their political actions and statements. However, there is no plurality of public domain and counter-public sphere against the main public sphere, only interconnected nodes of public and counter-publics, debates and countered public debates that increase the scope of debate, disputes, troubles, and solutions and extend the possibility of quality of arguments (Rasmussen, 2016). The networked public sphere has brought a vivid democratic transformation in society, as unlike the Habermasian public sphere, it is not built on normative disciplines, but rather, on network-enhancing digital technologies. Citizens are no more passive recipients of information, rather, they actively respond to the local and national political affairs of their state. They are no longer passive observers but rather are substantial members to be involved in finding the solutions to the political and the subjects involved in the political communication of their society (Benkler et al, 2013)

The Conceptualisation of Digitally Networked Participation

The core premise to accepting digitally networked political involvement as a genuine form of political participation is the acknowledgement that the activation of one’s personal social media account via digital media with the purpose of mobilising others for political and social causes is considered a kind of political participation with a different manifestation.

Studies designed to measure the digitally networked acts of participation have exposed that a huge number of individuals are participating in politics through social networking sites (Xenos et al., 2014), but also among them are the traditionally disengaged citizens, for the new media is the only inventory to participate in politics (Earl, 2014). Thus, it can be said that engagement through digitally networked acts of participation has been a new mode of political partaking that is not only mechanically analogous to physical political involvement but also captures a different concept of citizenship to be engaged in politics (Bennet, 2012).

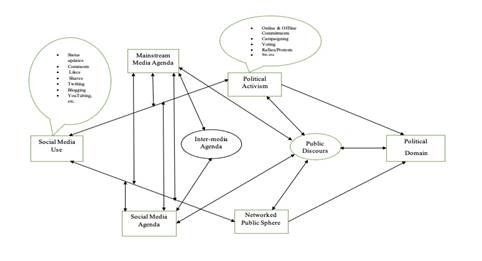

Figure 1

Conceptual Diagram of the Networked Public Sphere.

Social Media Use and Political Activism

The first crucial determinant of this diagram is the citizens’ social media use for political purposes, which has been conceptualized as having linked with infusing political activism among them consequently emerging a networked public sphere that influences the political domain of the society. It is essential to recognize the appearance of different forms of citizenship in order to understand the link between the two components being discussed here (Xenos et al., 2014). The recent forms of political participation are radically different to old forms of citizen participation in politics and public life (Bennet, 2012; Dalton et al., 2009). Traditional styles of political participation have been replaced by the personalized politics of participation through social media (Bennet, Wells, & Freelon, 2011).

The conceptualized diagram of the networked public sphere talks about the assumption of the connection between social media use and political activism. Currently, social media platforms provide high-tech communication means to acquire and transmit political information, and participate in political activities online (Vitak et al., 2011). The Internet has been identified as the alternative public sphere that offers different platforms for political debates among the masses.

The Interplay between Mainstream Media and Social Media in Networked Public Sphere

As mentioned in the diagram, another important factor of the conceptualized networked public sphere is the inter-media agenda that come into existence due to the interplay of social media and mainstream media agendas. Thanks to technological convergence, the boundaries between old and new media have been blurred (Jenkins et al., 2006) and social media users have become prosumers (those who consume and produce content at the same time). The Internet and social media technologies have established a hybrid environment in which there is a huge interplay between old and new media (Chadwick, 2011; Fenton, 2009). This interplay of inter-media agenda setting is one of the determinants of the current conceptual framework of the study that helps and strengthens the relationship between social media use in stimulating political activism among youth and helping to establish a networked public sphere.

The established power relations have been changed altogether and scholars like McNair (2006) have witnessed a paradigm shift in both mass media and politics. The age-old role of mainstream media in setting the agenda of the world has been shared by online communication (Meraz, 2009). There is a huge rebroadcasting of content that has been seen in mainstream media and social media across the world. The user-generated contents serve the mainstream media to break exclusive stories. Mainstream journalists, by joining different social media networks, keep in touch with common users. These networks act as news sources and great avenues for breaking news (Bunz, 2010). Subsequently, the new media-networked groups have added a significant impact on the content building process of the mainstream media (Newman, 2009). This co-orientation of contents between different media news outlets is also called "churnalism" which has the economical origin as its most cost-effective practice and requires fewer resources while obtaining one’s own lead (Raymond et al., 2017).

The co-orientation of contents also has some socio-psychological reasons as well. Journalists are often confused while dealing with the newsworthiness or news values of stories when they must decide which story to cover. Despite having gone through professional training and socialisation with the newsroom and the field, the single journalist or his organisation (Harcup & O' Neill, 2016), while practising the criteria of newsworthiness, remains perplexed. Eyeing other media outlets' coverage, then, can be beneficial to overcome their suspicions as to which news items are important enough to be covered on a particular day (Raymond et al., 2017). The Internet was at the age of infancy at the end of the 20th century during the development of inter-media agenda-setting theory, but in the latest decades, the influence of the Internet and social media technologies is profound. With the introduction of the Internet, news websites, and social media; the way information regarding news stories is gathered; and the way news stories are made and circulated has altogether been changed. This contemporary news scenario is characterised as ‘liminal’, ‘hybrid’, and ‘ambient’ (Chadwick, 2013; Harmida, 2014; Papacharissi, 2015); terms that refer to a situation in which no fixed properties can be assigned to any media platform and its content. All these media share the same kind of features, which once originated from one medium in the past (Raymond et., 2017). For instance, news website articles now share video clips, that originated from television. Similarly, journalists now are sharing their information gatekeeping role with the people previously recognized as the audience and are now in a position to manufacture and circulate their own version of stories via social media (Rosenstone, 2006). Their contents are used in journalists' stories, hence making the audience co-producers of the news stories (Bruns & Highfield, 2012).

According to Reberts et al., (2002), online media has become the new mass media. The users, through online communication (e.g., Facebook, blogs, Twitter), are able to shape the debate and set the agenda for society. The users, by sharing, discussing, and debating political issues, which are not covered by the conventional media, influence the agenda of the mainstream media (McNair, 2006). As far as the agenda-setting role of media is concerned, scholars (e.g., Bruns, 2005; Cardoso, 2008) agreed that social media; by replacing the mainstream media has turned as the core agenda compositor of society as these concerns are later picked up by the mainstream media and spread to the audience. Hence, it can be inferred that it is the new media that set the agenda of the mainstream media.

Social Media Use, Networked Public Sphere,and Public Discourse

Public discourse is another cardinal variable in the conceptualized networked public sphere reflected in the diagram above. It is a world that, if in limited respects, brings us closer to Habermas’s idea of the public sphere. The networked public sphere holds the democratic ideal of a Habermasian public sphere that allows people to interact with one another, exchange ideas and information, and debate on public matters without fear of any counterstroke from the economic and political powers (Beers, 2006). The online world of independent news media provides interactive opportunities to online communities for a more in-depth understanding of social and political issues. Unfettered media that provides a free marketplace of ideas, based on reason, helps to prosper the democratic norms in the country.

The most crucial aspect of the networked public sphere is to generate public discourse on societal issues (Cogburn & Espinoza, 2011). Yinjiao et al., (2016) believe the new form of networked public sphere exercises pressure on the political domains of society by generating a public discourse. Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet (1944), assume that those who are actively engaged in political debates are more likely to be engaged in political actions. According to Schmitt-Beck (2008), social media offer a variety of opportunities to generate public discourse. Valenzuela (2013) views that social media enriches the political learning of the users and enables them to participate in the political process more often.

Technology today has provided potential for social media to act as a public sphere in the networked atmosphere (Beers, 2006). The structure of the networked public sphere is based on social media. Without social media, the power and shape of the networked public sphere would have been quite different. Therefore, it is claimed that social media users are in a position where they are more exposed to political information which leads them to have an online political discussions among other users. Hence, they are likely to be engaged in physical political discussions and debates, thus generating a discourse that eventually affects political organisations.

Conclusion

Networked news media are interactive in nature, easy and inexpensive to produce content, global in reach, and viral in distribution. All these determinants make social media a natural host for the public sphere that generates a public discourse, which Habermas has defined. Therefore, social media avenues naturally are fertile grounds to be independent media that are challenging the impact and authority of mainstream media. All these factors establish a networked public sphere, which generates a discourse that eventually affects political organisations. The study concludes that a new form of the networked public sphere has been formed where social media is considered a dominant factor in contemporary politics. These elements are crucial for social media users to debate among themselves regarding political matters and generate a public discourse that influences the political domains of society.

References

- Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: how social production transforms markets and freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Bennett, W. L., Wells, C., & Freelon, D. (2011). “Communicating Civic Engagement: Contrasting Models of Citizenship in the Youth Web Sphere.†Journal of Communication 61(5), 835–856.

- Bennett, W. L. (2012). The personalization of politics: political identity, social media, and changing patterns of Participation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 644(1), 20-39.

- Beers, D. (2006). The public sphere and online independent journalism. Canadian Journal of Education, 29(1), 109-130.

- Bruns, A. (2005). Gate watching collaborative online news production. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Cardoso, G. (2008). From mass to network communication: Communication models and the informational society. International Journal of Communication, 2, 578-630.

- Castells, M. (2000). The rise of the network society: the information age: economy, society, and culture (2nd ed. Vol. 1). Hobokon, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Castells, M. (2008). Communication power. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system, politics and power. In A. Chadwick. (Ed.), Digital Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cogburn, D. L., & Espinoza-Vasquezb, F. K. (2011). From networked nominee to networked nation: examining the impact of Web 2.0 and social media on political participation and civic engagement in the 2008 Obama Campaign. J. Political Market, 10, 189-213.

- Dalton, R. J., Sickle, A. V., & Weldon, S. (2009). The individual-institutional nexus of protest behaviour. British Journal of Political Science. (40), 51-70.

- Earl, J. (2014). Something old and something new: a comment on “new media, new civicsâ€. Policy & Internet, 6(2), 169-175.

- Habermas, J. (1962). The Structural transformation of the Public Sphere. MIT Press

- Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Habermas, J. (2006). Political Communication in Media Society: Does Democracy Still Enjoy an Epistemic Dimension? The Impact of Normative Theory on Empirical Research. Communication Theory, 16: 411- 426.

- Harcup, T., & O’Neill, D. (2017). What is news? Journalism Studies, 18(12), 1470-1488.

- Hermida, A. (2014). Twitter as an ambient news network. In Katrin., Bruns., Axel., Burgess., Jean., Mahrt., Merja. & P. Cornelius (Eds.), Twitter and Society (359-372): Peter Lang Inc. New York.

- Lazersfeld, P. F., Berelson, B., & Gaudet, H. (1944). The people's choice: how the voter makes up his mind in a presidential campaign. New York: Columbia University Press

- mcNair, B. (2006). Cultural chaos: journalism, news, and power in a globalized world. England; New York: Routledge

- Meraz, S. (2009). Is there an elite hold? Traditional media to social media agenda setting influence in blog networks. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 14(3), 682-707.

- Papacharissi, Z. (2002). The virtual sphere: The internet as a public sphere. New Media & Society, 4(1), 9– 27.

- Papacharissi, Z. (2015). Toward new journalism(s). Journalism Studies, 16(1), 27- 40.

- Roberts, M., Wanta, W., & Dzwo, T. H. (2002). Agenda setting and issue salience online. Communication Research, 29(4), 452-465.

- Rojas, H., & Puig-i-Abril, E. (2009). Mobilizers mobilized: information, expression, mobilization and participation in the digital age. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(4), 902-927.

- Rosenstone, S. J. (2006). The people formerly known as audience. Press Think. Retrieved from

- Valenzuela, S. (2013). Unpacking the use of social media for protest behavior: the role of information, opinion expression and activism. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(7), 920-942.

- Vitak, J., Zube, P., & Smock, A. (2011). It’s complicated: Facebook users' political participation in the 2008 election. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14(3), 107-114.

- Xenos, M., Vromen, A., & Loader, B. D. (2014). The great equalizer? Pattern of social media use and youth political engagement in three advanced democracies. Information Communication & Society, 17(2), 151-167.

- Yang, G. (2010). The power of the Internet in china: citizen activism online. Columbia University Press.

- Yinjiao, Y., Ping, X., & Zhnag, M. (2016). Social media, public discourse and civic engagement in modern China. Thematics and Informatics, 34, 705-714

Cite this article

-

APA : Mahmood, Q., Gull, Z., & Alam, R. N. (2022). Re-Conceptualizing Public Sphere in the Digital Era: From Habermas' Public Sphere to Digitally Networked Public Sphere. Global Digital & Print Media Review, V(I), 206-214. https://doi.org/10.31703/gdpmr.2022(V-I).20

-

CHICAGO : Mahmood, Qasim, Zarmina Gull, and Rao Nadeem Alam. 2022. "Re-Conceptualizing Public Sphere in the Digital Era: From Habermas' Public Sphere to Digitally Networked Public Sphere." Global Digital & Print Media Review, V (I): 206-214 doi: 10.31703/gdpmr.2022(V-I).20

-

HARVARD : MAHMOOD, Q., GULL, Z. & ALAM, R. N. 2022. Re-Conceptualizing Public Sphere in the Digital Era: From Habermas' Public Sphere to Digitally Networked Public Sphere. Global Digital & Print Media Review, V, 206-214.

-

MHRA : Mahmood, Qasim, Zarmina Gull, and Rao Nadeem Alam. 2022. "Re-Conceptualizing Public Sphere in the Digital Era: From Habermas' Public Sphere to Digitally Networked Public Sphere." Global Digital & Print Media Review, V: 206-214

-

MLA : Mahmood, Qasim, Zarmina Gull, and Rao Nadeem Alam. "Re-Conceptualizing Public Sphere in the Digital Era: From Habermas' Public Sphere to Digitally Networked Public Sphere." Global Digital & Print Media Review, V.I (2022): 206-214 Print.

-

OXFORD : Mahmood, Qasim, Gull, Zarmina, and Alam, Rao Nadeem (2022), "Re-Conceptualizing Public Sphere in the Digital Era: From Habermas' Public Sphere to Digitally Networked Public Sphere", Global Digital & Print Media Review, V (I), 206-214

-

TURABIAN : Mahmood, Qasim, Zarmina Gull, and Rao Nadeem Alam. "Re-Conceptualizing Public Sphere in the Digital Era: From Habermas' Public Sphere to Digitally Networked Public Sphere." Global Digital & Print Media Review V, no. I (2022): 206-214. https://doi.org/10.31703/gdpmr.2022(V-I).20